Moth Edrei

Natalia Goncharova and the Orientalization of the Jewish People

Natalia Goncharova has been oft-overlooked as an important figure within the Russian avant-garde of the 20th century. Both her and her lifelong partner, Mikhail Larionov were concerned with creating a “new” Russian art style that was distinctly separate from the artwork of the West. Despite this, their artwork can be seen as reactionary and therefore intrinsically defined by the notion of the Other. This is a reversal of the classical definition of the Orient as coined by Edward Said, in which the Orient is defined through its dominance by the West. Both Goncharova and Larionov portrayed Jewish people within their work, and often within a primitive style. Through the use of this primitive style, however unwillingly, Goncharova and Larionov contributed to the orientalization of the Jewish people. It has been argued that both Goncharova and Larionov held a sympathetic view of the Jewish people— however, they painted them from an outsider, Christian perspective, rendering them an oddity within Russia’s complex landscape.

Natalia Goncharova, Jews (Shabbat), 1911, Oil on canvas. 137 x 118 cm. State Museum of Fine Art, Republic of Tatarstan, RussiaHere, Goncharova chooses a similarly Primitivist, but altogether different style to represent Jewish people. Her choice of subject mirrors the acts of many French painters in the 1800s, who would travel to Morocco and other areas of the Orient and paint the Jewish people who resided there. However, instead of looking outside her homeland, Goncharova is looking within it— creating a new form of ethnographic research.

Much of Goncharova’s work can be categorized as neo-primitivism, with her turning back towards the east to develop her style as early as 1911. Cheryl Kramer, within Natalia Goncharova: Her Depiction of Jews in Tsarist Russia observes that there is an implication here that the figures within the frame were prevented from observing the Sabbath— it is of note that the women are picking and carrying flowers, an act specifically forbidden. While this piece can be seen as somewhat sympathetic, the artistic style reduces the figures to flat planes and blocks of unnatural colors, rendering them unfamiliar and strange to a Russian audience.

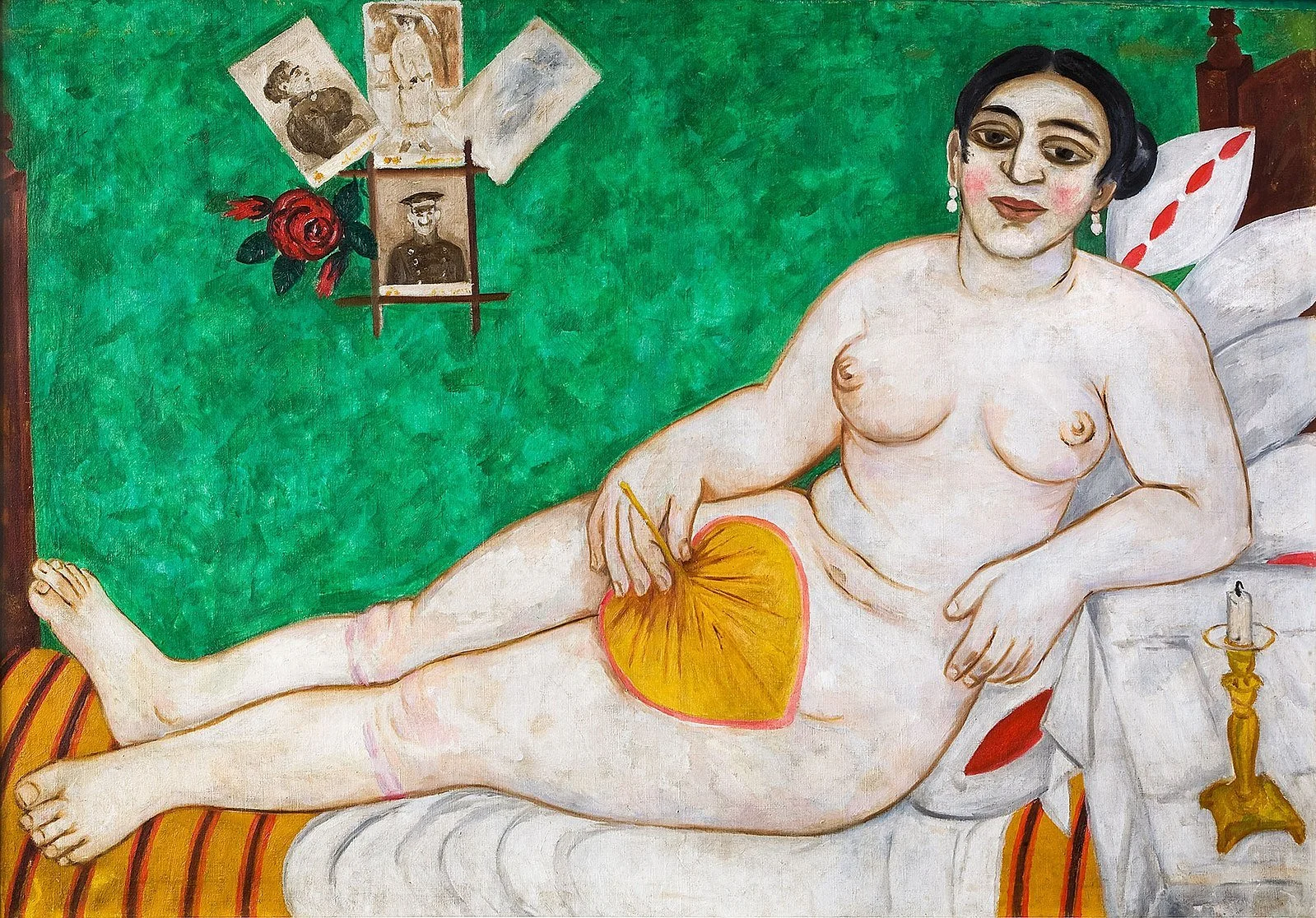

Natalia Goncharova, Jewish people in the Street: A Jewish Shop, 1912, Oil on canvas. The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, RussiaMikhail Larionov, Jewish Venus, 1912, Oil on canvas. 104.8 x 147 cm. Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts, Yekaterinburg, RussiaLarionov painted a series of Venuses, of varying nationalities. He publicly announced this project in the Russian newspaper Stolichnaya Molva in October of 1912, where he expressed his desire to paint a venus of varying ethnicities, including Roma, Greek, Chinese, Black, Indian, Ukrainian, and more. However, he ultimately only produced four: a Moldavian, Roma, Katsap (Russian), and a Jewish Venus. While he proclaimed this project was to celebrate beauty of all nationalities, it is notable the way he ethnicized the figures face, emphasizing her dark hair and brows. She also has comically large hands and feet, unusual for a figure in this position.

Mikhail Larionov, Katsap Venus, 1912, Oil on canvas. 99.5 x 129.5 cm. The Nizhny Novgorod State Arts Museum, Nizhny Novgorod, RussiaInterestingly, katsap is a Ukranian word— a derogatory term for Russian. While it is difficult to know why Larionov, a Russian, would use such a term, this painting does indicate that he participated in a sort of self-orientalization. It is hard not to associate the figure in the frame with Larionov himself, due to having the same ethnicity. Her hands and feet are darker than the rest of her body, almost as if to emphasize her peasant class— perhaps she has been laboring in the hot sun.

The Jews of Vilna at the Turn of the Century, Photograph, Yad Veshem Photo Archives 6902/2While this photograph portrays Lithuanian Jews, they lived during the same period as Goncharova and Larionov. The contrast between their actual dress and the dress that Goncharova chooses to place her subjects in is stark. In addition, one can see that their features are not “ethnicized,” — Jewish people did not have a specific “look,” and to imply so is antisemitic.

Moth Edrei

(they/them)

Art History ‘22

Moth Edrei is an aspiring art historian.