Picturing the Port: Images of Philadelphia Longshoremen

by Joanna Platt

I am currently investigating the representation of labor in art, the economics of art and production, especially related to class issues. While there are undeniably socialist undertones to this research, I am interested in the broader social history of art, the materials and methods of its production, and its reception within the culture. I am attracted to the points in history when poor and working-class artists had funding and access to resources. Specifically, my research focuses on representations of American working-class history in the Works Progress Administration-supported art of the 1930s and the connections to Philadelphia through The Fine Print Workshop.

I was drawn to this photo from The Library Company because it is an image of dock workers taken in approximately 1935, one of the peak years of the WPA. While this image does not seem to connect directly to the WPA, it tells a parallel story of progressive-era utopian policy. When the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) unionized the longshoremen in Philadelphia, they institutionalized diversity and inclusion, creating an unparalleled opportunity for African American Stevedores. The IWW was an anarcho-socialist organization whose ultimate goal was to destroy the capitalist system, bringing control of the means of production to the workers. However, these revolutionary tendencies were tabled in Philadelphia in favor of retaining union control over the docks. The IWW only remained in power on the docks from 1913-1923; however, the policies of inclusion and diversity they implemented remained in place until at least the 1970s when containerization shifted the industry.

Photographer Unknown, The Port, Philadelphia, Loading ships from Cars, Black and White Gelatin Silver Print, 7.5 inches by 9.5 inches, circa 1935. Photo courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia.

LABEL

This photo was taken at The Port of Philadelphia, a Delaware River shipyard in Port Richmond. The Reading Company built the Port of Richmond in the 1850s to connect its trains to ships and barges to export coal. By the early 1900s, when this photo was taken, Port Richmond was a booming industrial area filled with immigrant labor that worked in the factories and along the river. This photo depicts longshoremen or stevedores, classified as unskilled laborers, loading iron pipe onto a ship. Today’s cranes and container ships have automated many of these manual labor jobs, relegating this backbreaking labor to the gelatin silver prints of history. However, this was once a lucrative job. While these jobs are demanding and low-skilled, they are not necessarily low paying as they are often highly unionized, and a strike by these workers can completely shut down global commerce.

COUNTERLABEL

This image is striking in the diversity of workers represented, which was a direct result of union activities along the river. Early attempts to unionize the longshoremen failed due to a constant influx of immigrants and Black workers willing to work under any conditions. The competition was fierce for unskilled jobs, and racial tensions were stoked by employers with a vested interest dividing their workers. The Industrial Workers of the Word (IWW) organized a strike of the longshoremen of Philadelphia on May 14, 1913. A syndicalist organization, the IWW was committed to abolishing racial distinctions in hiring practices. Over half of the 4,000 striking workers were African American solidifying their position on the docks. The IWW would remain in power in the ports for the next decade, and their influence on workers would be felt, with Philadelphia maintaining diversity amongst the dockworkers into the present.

This photo was taken in 1923, ten years after the admission of Black workers into the union. While this image could represent progress, the torn clothing, emphasized by a racist manuscript note by the photographer on the verso, would suggest that more than just union regulations were needed to eradicate the long history of racial animosity on the docks. By the mid-nineteenth century, longshoring, which had previously been a predominantly Black occupation, was inundated with Irish immigrants who battled violently with African Americans for jobs. In the trades, white workers took advantage of prejudice. Many efforts were made to keep Black workers out of industry including early trade unions writing the word “white” under their qualifications for admission. Companies would refuse to hire non-union men, and the unions would refuse to admit Black men.

G. Mark Wilson, 2nd and Brown St. A stevedore, a family, Black and White Gelatin Silver Print, 4 ¾ ” x 3 ¾,” circa 1923. Photo courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia.

This drawing by Ralph Chaplin depicts a group of union men joining together to create one giant fist, symbolizing their combined power. Their other hands hold the tools of their trades. The IWW aimed to unionize the unskilled workers that often fell through the cracks of the major unions. The IWW was anti-capitalist and differed from the more traditional trade associations of the time, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which had a closer relationship with business interests. Early in their history, the AFL and the established unions did not permit Black workers to join their unions. Groups like the IWW attempted to bridge the gap between the working class races, which is why they were seen as so dangerous by capitalist interests intent on creating division between the races to maintain labor control.

Ralph Chaplin, The Hand That Will Rule the World, 1917.

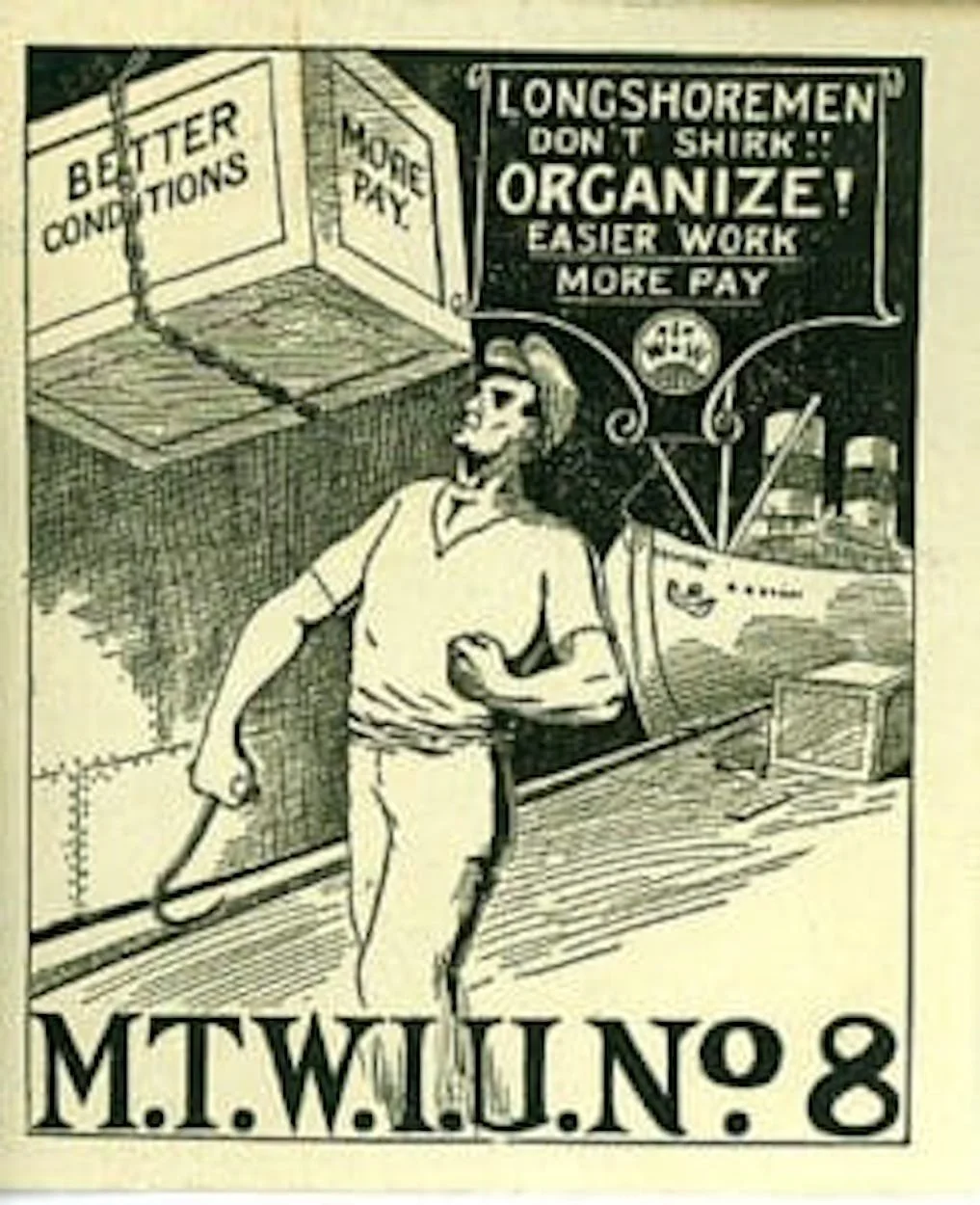

This poster is a call to arms for the IWW Local 8 longshoremen strike of 1920. Depicted in a style not dissimilar to war propaganda of the time, the Union man, muscles exposed and rippling, makes great strides while holding his cargo hook. While this strike helped Local 8 gain new members, it ultimately failed in its demands for an eight hour day. While the 1920s marked the IIWW’s decline, the ideals of the union remained extant in the policies of later unions.

Artist Unknown, MTWIU Local 8 1920 Strike Poster, circa 1920.

The importance of this institutionalized diversity can be seen in this aquatint by Dox Thrash. Depicting a similar scene to the Library Company photograph, Pier 27 was created in the WPA sponsored Fine Print Workshop. Dox Thrash was an African American artist with a degree from the Art Institute of Chicago; however, until his employment with the WPA, he was often consigned to the lowest forms of labor because of his race. Because WPA-funded programs forbid discrimination based on gender and race, they offered unparalleled opportunities for African Americans and women, exposing the public to a myriad of new images and ideas.

Dox Thrash, Pier 27, Aquatint on Paper, 5”x 8 ¼,” circa 1937.

Picturing the Port: Podcast

“Today I want to talk about a photograph from the African Americana Collection at the Library Company of Philadelphia. It is a Black and White Gelatin Silver Print, 7.5 inches by 9.5 inches, titled The Port, Philadelphia, Loading ships from Cars. The title of the photo was taken from a note on the back, reinforcing the importance of the activity taking place. The library company has given it an approximate date of 1935 based on the medium and content…”

Joanna Platt

Art History / 2027

Joanna Platt (she/her) MFA, University of the Arts, Philadelphia, PA BFA, Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Joanna Platt is A Ph.D. student specializing in modern and contemporary art history. Her primary interests are the representation of labor and the economics of art and production, especially regarding issues of class and social status. Joanna is currently researching Philadelphia’s connections to the Works Progress Administration-sponsored Fine Art Project, specifically issues of inclusivity in the Fine Print Workshop.