Irina Kasharsky-Segal

Mysticism and the Female Perspective: The Anti-Surrealism of Surrealist Remedios Varo

Varo’s unprecedented approach to breaking the molds of patriarchal surrealism and using her “self” as the subject and study of her subject matter, is meant to only brush on the surface of her reliance and belief in the mystical realm, in the realm of magic equations, algorithms, and endless layers of consciousness. Varo refused to be confined by the patriarchal bounds of the surrealist movement, and whether it was intentionally decided by her or not, it is undoubtedly a surrealist revolution she started. Varo along with a few other female surrealists from her time and close circle, began to place the female as the object and subject of the work—not as a femme fatale, or femme enfante, or femme anything through the gaze of the male; but as a female taking ownership of herself, her existence, her importance to the order of all things, and her view of the world around her, rather that having her be seen through the male gaze as the subject of the male interpretation and appropriation of her femininity. Varo used layers upon layers of iconography, hidden messages and unsolvable riddles in her work, all connected through themes of the supernatural, scientific and alchemy. Varo was a prolific artist and her work has, and will continue to inspire us, challenge us, trick us and play a joke on us that may leave one scratching their head with confusion, or can result in a laugh out loud moment when you make that connection and say “Oh, I see what you did there.”

Horna, Kati. Untitled. Photograph of Remedios Varo. Gelatin Silver Print. 1962. Museum of Modern Art, New York.Toward the Tower is more openly autobiographical for Varo. Varo rejected Catholicism and felt it was claustrophobic; leaving her Catholic school in Madrid, to pursue her love of art at the Royal academy of Fine arts. In this composition, being led by the male figure and the nun, the young ladies all appear to gaze in the same direction, except for one that defies the order of the crowd, one who interacts directly with the viewer and gazes forward into our space. It is easy to believe this is Varo herself showing us her story, or the start to her story and the importance of her rejecting these common female structures at

the time, and instead taking her own path, and making her own choice about her life, her personal and professional pursuits. So much of Varo’s work, if not all of it, is metaphorically autobiographical, and exploring and understanding the interplay between her life and her art is essential to understanding her significance and her tremendous contribution to the Female voice and the female perspective of self.

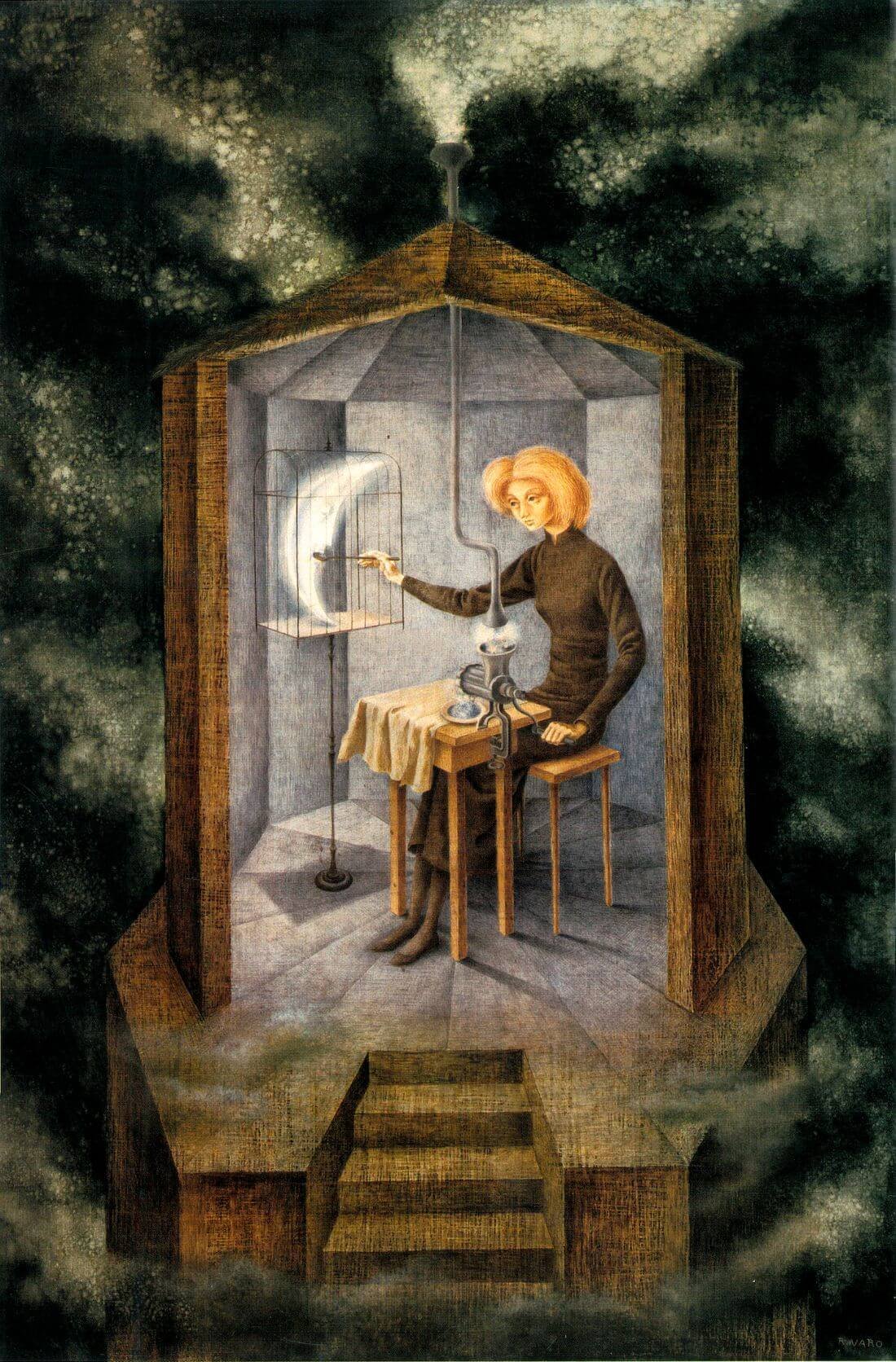

Varo’s Celestial Pablum shows an enclosed floating space, with a figure sitting at the table, bearing strong resemblance to Varo’s own features, which is another indication that Varo’s work bears deep autobiographical significance. In the enclosed room, we see the figure with her appearing to be, disenchanted gaze as she methodically places the utensil into the mouth of the caged moon, -- the viewer can infer that this is a tedious and constant activity for the woman, repetitive and predictable, easily translated through her gaze and body language. The woman is grinding or holding a mysterious machine that expresses the steam at the top into the universe and at the same time using that steam to create sustenance for the woman to feed the moon. Varo shows us that everything, life, and the order of things, even the order of the universe is a result of the female acting upon it; the woman is the center to sustenance and without her, the moon will not exist, nor will the universe around it.

Horna, Kati. Untitled. Photograph of Remedios Varo. Gelatin Silver Print. 1962. Museum of Modern Art, New York.Varo, Remedios. Celestial Pablum. 1958. Oil on canvas, 92 mm. x 62 mm. Private Collection. Like her Untitled photograph of Varo in her studio, Kati Horna uses Varo as the “Surrealist Self” as both the subject of, and the Surrealist object of the composition. Horna’s frequent photographs of Varo are an indication of their close relationship with each other and fellow Surrealist, Leonora Carrington, who is also responsible for the construction of the mask worn here by Remedios Varo. We see Varo turned to the side, engaging us the viewer, while at the same time disengaging from, and looking out to another space where we are not.

There are a series of these photographs; where Varo is wearing this same mask, but each time positioned differently. In choosing this image, it is relevant to note that the mask is facing forward into the space of the viewer, and whose gaze directly confronts our own. In this case, I believe it may be that same riddle present here, that we find permeating through the work of Varo, Carrington and Horna herself, providing the viewer with the seemingly subtle, but outwardly clever subtextual criticism and confrontation of the role of the woman, and having to wear and hide behind a mask or image of herself that is put upon her. In this case, the mask is not created by the patriarchal boundaries, but by a woman to be worn by a woman and then photographed by a woman. In this regard, this photograph shows the woman’s rejection of the masks previously put upon her and taking a sort of “matters into her own hands” approach.

Kati Horna. Untitled (Remedios Varo in her studio), ca. 1957-58. Museum of Modern Art, New York.This photograph of Remedios Varo was taken by her dear friend and female surrealist photographer, Kati Horna. Set in Varo’s studio, six years prior to her untimely passing, this photograph shows Varo in deep thought and contemplation. The composition of this photograph is particularly important in that it mimics Varos figures in her work. The figure or subject, in this case, Varo herself, overpowers the composition, where the viewer is forced to first confront the figure and the surrounding objects and setting is secondary. Varo’s gaze is interacting with the viewer, in that she appears to gaze not directly at us, but off to the side, which makes this photograph very much an homage to Varo’s work and the way she typically renders her figures, engaging with the viewer but very much detached and appearing isolated. Varo is photographed in her studio as the expert in her craft, leaning against her easel with her painting, and reminiscent of the figures in her own work, which are often rendered in workshops or enclosed spaces. This photograph can very much be interpreted as the answer to the riddle of Varo’s work; was she in fact representing herself as the subject of her work, and were the figures elements of herself, in fact were they all images in the likeness of Varo, therefore each piece holding autobiographical significance? It is here in this photograph, like in the work of Varo, where we see the female self through the eyes of the female perspective as was the revolution in surrealism that both Varo and Horna actively initiated and participated in. This representation of Varo is indicative of the strong relationship between Varo and Horna, and their influence on one another.

Varo, Remedios. Exploration of the sources of the Orinoco River. 1959. Oil on Canvas, 45.7 x 40 cm. Private Collection. Varo was determined to separate and distance herself from the Patriarchal Surrealist boundaries, set out by her male counterparts, and instead created a style, a movement of her very own. In Varo’s work, the female became the subject of the work, instead of an attribute to the composition. In Exploration of the Sources, we see another one of Varo’s famous fantastical machines, holding the woman and confining her, but at the same time enabling her to move. The figure holds all the strings and despite the instability of the vessel, she alone has the means to operate it.

Irina Kasharsky-Segal

(she/her)

Art History ‘22

For the last 17 years, I embarked on a journey of discovery, engagement and forming connections with different communities of artists, and had the opportunity to participate in creating meaningful pieces alongside them. Working with art makers of all abilities brought to light various questions in regards to what art can do and perhaps should do. I hope to continue making a difference for art makers that have been under-valued, under-represented and overlooked.